- Home

- Beverly Cleary

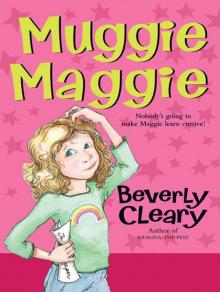

Muggie Maggie

Muggie Maggie Read online

Beverly Cleary

Muggie Maggie

Illustrated by

Tracy Dockray

To a third-grade girl who wondered why

no one ever wrote a book to help

third graders read cursive writing

Contents

Chapter 1

After her first day in the third grade, Maggie Schultz…

Chapter 2

The next day, after the third-grade monitors had led the…

Chapter 3

Maggie began to enjoy cursive time. She experimented with letters…

Chapter 4

Maggie had grown bored with not writing cursive, but by…

Chapter 5

Later that week, Mr. Schultz brought Maggie a present from Ms. Madden…

Chapter 6

One morning, Maggie noticed Mrs. Leeper whispering with other teachers in…

Chapter 7

For the next few days Maggie was a busy message…

Chapter 8

On Monday, Maggie looked at the words Mrs. Leeper had written…

About the Author

Other Books by Beverly Cleary

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Chapter 1

After her first day in the third grade, Maggie Schultz jumped off the school bus when it stopped at her corner. “Bye, Jo Ann,” she called to the girl who was her best friend, sometimes. “See you tomorrow.” Maggie was happy to escape from sixth-grade boys who called her a cootie and from fourth-grade boys who insisted the third grade was awful, cursive writing hard, and Mrs. Leeper, the teacher, mean.

Her dog, Kisser, was waiting for her. When Maggie knelt to hug him, Kisser licked her face. He was a young, eager dog the Schultzes had chosen from the S.P.C.A.’s Pick-a-Pet page in the newspaper. “A friendly cockapoo looking for a child to love” was the description under his picture, a description that proved to be right.

“Come on, Kisser.” Maggie ran home with her fair hair flying and her dog springing along beside her.

When Maggie and Kisser burst through the kitchen door, her mother said, “Hi there, Angelface. How did things go today?” She held Kisser away from the refrigerator with her foot while she put away milk cartons and vegetables. Mrs. Schultz was good at standing on one foot because five mornings a week she taught exercise classes to over-weight women.

“Mrs. Leeper is nice, sort of,” began Maggie, “except she didn’t make me a monitor and she put Jo Ann at a different table.”

“Too bad,” said Mrs. Schultz.

Maggie continued. “Courtney sits on one side of me and Kelly on the other and that Kirby Jones, who sits across from me, kept pushing the table into my stomach.”

“And what did you do?” Mrs. Schultz was taking eggs out of a carton and setting them in the white plastic egg tray in the refrigerator.

“Pushed it back.” Maggie thought a moment before she said, “Mrs. Leeper said we are going to have a happy third grade.”

“That’s nice.” Mrs. Schultz smiled as she closed the refrigerator, but Maggie was doubtful about a teacher who forecast happiness. How did she know? Still, Maggie wanted her teacher to be happy.

“Kisser needs exercise,” Mrs. Schultz said. “Why don’t you take him outside and give him a workout?” Maggie’s mother thought everyone, dogs included, needed exercise.

Maggie enjoyed chasing Kisser around the backyard, ducking, dodging, and throwing a dirty tennis ball, wet with dog spit, for him until he collapsed, panting, and she was out of breath from running and laughing.

Refreshed and much more cheerful, Maggie was flipping through television channels with the remote control, trying to find funny commercials, when her father came home from work. “Daddy! Daddy!” she cried, running to meet him. He picked her up, kissed her, and asked, “How’s my Goldilocks?” When he set her down, he kissed his wife.

“Tired?” Mrs. Schultz asked.

“Traffic gets worse every day,” he answered.

“Was it your turn to make the coffee?” demanded Maggie.

“That’s right,” grumped Mr. Schultz, half-pretending.

Other than talking with people who came to see him, Maggie did not really understand what her father did in his office. She did know he made coffee every other day because Ms. Madden, his secretary, said she did not go to work in an office to make coffee. He should take his turn. Ms. Madden was such an excellent secretary—one who could spell, punctuate, and type—that Mr. Schultz put up with his share of coffee-making. Maggie found this so funny that she always asked about the coffee.

“Did Ms. Madden send me a present?” Maggie asked. Her father’s secretary often sent Maggie a little present: a tiny bottle of shampoo from a hotel, a free sample of perfume, and once, an eraser shaped like a duck. Maggie felt grown-up when she wrote thank-you notes on their home computer.

“Not today.” Mr. Schultz tousled Maggie’s hair and went to change into his jogging clothes.

When dinner was on the table and the family, exercised, happy, and hungry, was seated, Maggie chose the right moment to break her big news. “We start cursive this week,” she said with a gusty sigh that was supposed to impress her parents with the hard work that lay ahead.

Instead, they laughed. Maggie was annoyed. Cursive was serious. She tossed her hair, which was perfect for tossing, waving, and curling to her shoulders, the sort of hair that made women say, “What wouldn’t you give for hair like that?” or, in sad voices, “I used to have hair that color.”

“Don’t look so gloomy,” said Maggie’s father. “You’ll survive.”

How did he know? Maggie scowled, still hurting from being laughed at, and said, “Cursive is dumb. It’s all wrinkled and stuck together, and I can’t see why I am supposed to do it.” This was a new thought that popped into her mind that moment.

“Because everyone writes cursive,” said Mrs. Schultz. “Or almost everybody.”

“But I can write print, or I can use the computer,” said Maggie, arguing mostly just to be arguing.

“I’m sure you’ll enjoy cursive once you start,” said Mrs. Schultz in that brisk, positive way that always made Maggie feel contrary.

I will not enjoy it, thought Maggie, and she said, “All those loops and squiggles. I don’t think I’ll do it.”

“Of course you will,” said her father. “That’s why you go to school.”

This made Maggie even more contrary. “I’m not going to write cursive, and nobody can make me. So there.”

“Ho-ho,” said her mother so cheerfully that Maggie felt three times as contrary.

Mr. Schultz’s smile flattened into a straight line. “Just get busy, do what your teacher says, and learn it.”

The way her father spoke pushed Maggie further into contrariness. She stabbed her fork into her baked potato so the handle stood up straight, then she broke off a piece of her beef patty with her fingers and fed it to Kisser.

“Maggie, please,” said her mother. “Your father has had a hard day, and I haven’t had such a great day myself.” After teaching her exercise classes in the morning, Mrs. Schultz spent her afternoons running errands for her family: dry cleaner, bank, gas station, market, post office.

Maggie pulled her fork out of her baked potato. Kisser licked his chops and looked up at her with hope in his brown eyes, his tail wagging. “Kisser is lucky,” she said. “He doesn’t have to learn cursive.” When her dog heard his name, he stood up and placed his front paws on her lap.

“Now you’re being silly, Maggie,” said her father. “Down, Kisser, you old nuisance.”

Maggie was indignant. “Kisser is not a nuisance. Kisser is a loving dog,” she informed her father.

“

Don’t try to change the subject.” Mr. Schultz, irritated with Maggie, smiled at his wife, who was pouring him a cup of coffee.

“Books are not written in cursive,” Maggie pointed out. “I can read chapter books, and not everyone in my class is good at that.”

Mr. Schultz sipped his coffee. “True,” he admitted, “but many things are written in cursive. Memos, many letters, grocery lists, checks, lots of things.”

“I can write letters in printing, and I never write those other things,” argued Maggie, “so I am not going to learn cursive.” She tossed her hair and asked to be excused.

Kisser felt that he, too, was excused. He trotted after Maggie and jumped up on her bed. As she hugged him, Maggie overheard her mother say, “I don’t know what gets into Maggie. Most of the time she behaves herself, and then suddenly she doesn’t.”

“Contrary kid,” said her father.

Chapter 2

The next day, after the third-grade monitors had led the flag salute, changed the date on the calendar, fed the hamster, and done all the housekeeping chores that third-grade monitors do in the morning, Mrs. Leeper faced her class and said, “Today is going to be a happy day.”

The third grade looked hopeful.

“Today we take a big step in growing up,” said Mrs. Leeper. “We are going to learn cursive handwriting. We are going to learn to make our letters flow together.” Mrs. Leeper made flow sound like a long, long word as she waved her hand in a graceful flowing motion.

She calls that exciting, thought Maggie, slumping in her chair.

“How many of you have ridden on a roller coaster?” asked Mrs. Leeper. Half the members of the class raised their hands. Mrs. Leeper wrote on the chalkboard:

“Many letters start up slowly, just like a roller coaster, and then drop down,” she said, and she traced over the first stroke of each letter with colored chalk. Then she went on to demonstrate how the roller coaster climbed almost straight up:

After the paper monitor passed out paper, the class practiced, not whole letters but roller-coaster strokes:

Maggie did as she was told until she grew bored and began to draw one long roller-coaster line that rose and fell, turned and twisted, and rose again. So many of the class needed help with their strokes that Mrs. Leeper did not get around to Maggie.

The next day, after strokes, the class practiced whole letters, some with loops that went up, some with loops that went down. This was difficult. The third grade frowned, worried, struggled, and asked Mrs. Leeper whether they were doing it right. Then they learned to connect letters with straight lines. Maggie went on drawing roller coasters until Mrs. Leeper noticed.

“Why, Maggie,” she said, “why haven’t you been working on your loops and lines?”

“I am working,” said Maggie, “on roller coasters.”

Mrs. Leeper looked thoughtfully at Maggie, who tried to look happy. “Roller coasters are not cursive,” said the teacher.

“I know,” agreed Maggie, “but I don’t need cursive. I use our computer.”

“Maggie, I think you had better stay after school so we can have a little talk,” said Mrs. Leeper.

“I have to catch my bus,” said Maggie with her sweetest smile.

That afternoon, Maggie examined cursive writing wherever she found it. “Why does your writing on the grocery list lean over backward?” she asked her mother. “Mrs. Leeper says letters should lean forward as if they were walking against the wind.”

“I’m left-handed, and my teachers didn’t show me how to turn my paper,” answered Mrs. Schultz.

“And what are those little circles floating around?” asked Maggie.

Her mother laughed. “When I was in junior high, girls often made circles instead of dots over their i’s. We thought it was artistic or something. I don’t really remember.”

That evening, Maggie stood at her father’s side as he wrote a letter on the computer. When he pulled the paper out of the printer, he picked up a pen and wrote at the bottom:

“What does that say?” asked Maggie.

“That’s how I sign my name,” said her father. “Sydney Schultz.”

“You didn’t close your loops,” Maggie pointed out. “You are supposed to close loops on letters that have pieces that hang down.” She had learned a thing or two in spite of herself.

“Oops,” said Mr. Schultz, and he closed his loops.

Chapter 3

Maggie began to enjoy cursive time. She experimented with letters leaning over backward and decorated with little circles, the way her mother dotted her i’s. She wrote messy g’s with long straight tails, the way her father made his y’s.

“Why, Maggie,” said Mrs. Leeper. “I find your cursive very untidy.”

“I’m writing like a grown-up,” Maggie explained.

The result was Mrs. Leeper’s asking Maggie’s mother to come to school for a conference. That day, Mrs. Schultz had to fill the gas tank of the car, go to the bank, buy paper for the computer, and take Kisser to the veterinarian for his shot—all this after teaching exercise classes in the morning. She was not smiling when she reached school, still wearing her warm-up suit. She handed Kisser’s leash to Maggie so she could take care of him during her conference with Mrs. Leeper.

Kisser was so happy to see a playground full of children that he wanted to jump up on everyone. Maggie had to hold on to his leash with both hands when her friends gathered around to ask why Mrs. Schultz was talking to the teacher.

Jo Ann answered for Maggie. “Maybe Mrs. Leeper wants her to be room mother or something.”

“I bet,” said Kirby on his way to the bus.

“What did she say?” demanded Maggie when her mother returned and everyone had boarded buses. “What did Mrs. Leeper say about me?”

“Down, Kisser!” Mrs. Schultz sounded cross. “Mrs. Leeper said you are a reluctant cursive writer who has not reached cursive-writing readiness, and perhaps you are too immature to write it.”

Maggie was indignant. “I am not!” she said. “I am Gifted and Talented.” Some people were Gifted and Talented, and some people weren’t. At least, that was what teachers thought. Maybe no one had told Mrs. Leeper how Gifted and Talented she was. Maggie’s mother drove home without saying one single word. Maggie hugged Kisser, who was so grateful that he licked her face, which she found comforting. Someone loved her.

For several days, just for fun, Maggie drew fancy letters at cursive time, and then Mrs. Leeper told her that Mr. Galloway, the principal, wanted to see her in his office. On her way, Maggie, filled with dread, dawdled as long as she felt she could get away with it.

“Hello there, Maggie,” said Mr. Galloway. “Sit down and let’s have a little talk.”

Maggie sat. She never enjoyed what grown-ups called “a little talk.”

Mr. Galloway smiled, leaned back in his chair, and placed his fingertips together like an A, with his thumbs for the crossbar. A printed A, of course. “Maggie, Mrs. Leeper tells me you are not writing cursive. Can you tell me why?”

Maggie swung her legs, stared at a picture of George Washington on the wall, nibbled a hangnail. Mr. Galloway waited. Finally, Maggie had to say something. “I don’t want to.”

“I see.” Mr. Galloway spoke as if Maggie had said something very important that required serious thought, lots of it.

“And why don’t you want to?” asked the principal after a long silence, during which Maggie studied the way he combed his hair over his bald spot.

“I just don’t want to,” said Maggie. “I use a computer.”

Mr. Galloway nodded as if he understood. “That’s all, Maggie,” he said. “Thank you for coming in.”

That evening, Mrs. Leeper telephoned Maggie’s mother to say that the principal had reported Maggie was not motivated to write cursive. “That means you don’t want to,” Mrs. Schultz explained to Maggie.

“That’s what I told him,” said Maggie, who couldn’t see what all the fuss was about.

“

Maggie!” cried her mother. “What are we going to do with you?”

“I’ll motivate you, young lady,” said Mr. Schultz. “No more computer for you. You stay strictly away from it.”

Mrs. Schultz had more to say. “Tomorrow, Maggie is to see the school psychologist.” She looked worried, Mr. Schultz looked grim, and Maggie was frightened. A psychologist sounded scary. Kisser understood. He licked Maggie’s hand to make her feel better.

As it turned out, Maggie loved the psychologist, who talked in a quiet voice and let her play with some toys while he asked gentle questions about her family, her dog, her teachers—nothing important. He asked about her times tables, and almost as an afterthought, he inquired, “How do you like cursive writing?”

“Okay,” answered Maggie, because he was a grown-up.

A couple of days later, Maggie’s mother said, “The school psychologist wrote us a letter.”

Maggie’s feelings were hurt. He had seemed like such a nice man. She had learned to be suspicious of letters from school. This was not the first.

Mrs. Schultz continued. “He says it will be interesting to see how long it will take you to decide to write cursive.”

“Oh,” said Maggie.

“How long do you think that will be?” asked Mrs. Schultz.

“Maybe forever,” said Maggie, beginning to wish she had never started the whole thing.

Chapter 4

Maggie had grown bored with not writing cursive, but by now the whole third grade was interested in her revolt. Each day, they watched to see whether she gave in. Her friends talked about it at lunchtime. In the hall, she overheard a fourth grader say, “There goes that girl who won’t write cursive.” Many people thought she was brave; others thought she was acting stupid. Obviously, Maggie could not back down now. She had to protect her pride.

Ramona Quimby, Age 8

Ramona Quimby, Age 8 Dear Mr. Henshaw

Dear Mr. Henshaw Beezus and Ramona

Beezus and Ramona A Girl from Yamhill

A Girl from Yamhill Ramona Forever

Ramona Forever Jean and Johnny

Jean and Johnny The Luckiest Girl

The Luckiest Girl Emily's Runaway Imagination

Emily's Runaway Imagination Ribsy

Ribsy Ramona the Pest

Ramona the Pest Socks

Socks Ramona's World

Ramona's World Strider

Strider The Mouse and the Motorcycle

The Mouse and the Motorcycle Henry and the Paper Route

Henry and the Paper Route Ramona the Brave

Ramona the Brave Henry Huggins

Henry Huggins Ramona and Her Mother

Ramona and Her Mother Ralph S. Mouse

Ralph S. Mouse Sister of the Bride

Sister of the Bride Henry and the Clubhouse

Henry and the Clubhouse Muggie Maggie

Muggie Maggie Runaway Ralph

Runaway Ralph Ramona and Her Father

Ramona and Her Father Henry and Ribsy

Henry and Ribsy Henry and Beezus

Henry and Beezus Two Times the Fun

Two Times the Fun Fifteen

Fifteen Mitch and Amy

Mitch and Amy