- Home

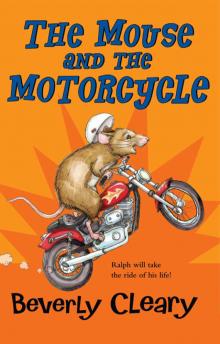

- Beverly Cleary

The Mouse and the Motorcycle

The Mouse and the Motorcycle Read online

Beverly Cleary

The Mouse and the Motorcycle

Illustrated by Tracy Dockray

Contents

1. The New Guests

2. The Motorcycle

3. Trapped!

4. Keith

5. Adventure in the Night

6. A Peanut Butter Sandwich

7. The Vacuum Cleaner

8. A Family Reunion

9. Ralph Takes Command

10. An Anxious Night

11. The Search

12. An Errand of Mercy

13. A Subject for a Composition

About the Author

Other Books by Beverly Cleary

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

1

The New Guests

Keith, the boy in the rumpled shorts and shirt, did not know he was being watched as he entered Room 215 of the Mountain View Inn. Neither did his mother and father, who both looked hot and tired. They had come from Ohio and for five days had driven across plains and deserts and over mountains to the old hotel in the California foothills twenty-five miles from Highway 40.

The fourth person entering Room 215 may have known he was being watched, but he did not care. He was Matt, sixty if he was a day, who at the moment was the bellboy. Matt also replaced worn-out lightbulbs, renewed washers in leaky faucets, carried trays for people who telephoned room service to order food sent to their rooms, and sometimes prevented children from hitting one another with croquet mallets on the lawn behind the hotel.

Now Matt’s right shoulder sagged with the weight of one of the bags he was carrying. “Here you are, Mr. Gridley. Rooms 215 and 216,” he said, setting the smaller of the bags on a luggage rack at the foot of the double bed before he opened a door into the next room. “I expect you and Mrs. Gridley will want Room 216. It is a corner room with twin beds and a private bath.” He carried the heavy bag into the next room, where he could be heard opening windows. Outside a chipmunk chattered in a pine tree and a chickadee whistled fee-bee-bee.

The boy’s mother looked critically around Room 215 and whispered, “I think we should drive back to the main highway. There must be a motel with a Vacancy sign someplace. We didn’t look long enough.”

“Not another mile,” answered the father. “I’m not driving another mile on a California highway on a holiday weekend. Did you see the way that truck almost forced us off the road?”

“Dad, did you see those two fellows on motorcycles—” began the boy and stopped, realizing he should not interrupt an argument.

“But this place is so old,” protested the boy’s mother. “And we have only three weeks for our whole trip. We had planned to spend the Fourth of July weekend in San Francisco and we wanted to show Keith as much of the United States as we could.”

“San Francisco will have to wait, and this is part of the United States. Besides, this used to be a very fashionable hotel,” said Mr. Gridley. “People came from miles around.”

“Fifty years ago,” said Mrs. Gridley. “And they came by horse and buggy.”

The bellboy returned to Room 215. “The dining room opens at six-thirty, sir. There is Ping-Pong in the game room, TV in the lobby, and croquet on the back lawn. I’m sure you will be very comfortable.” Matt, who had seen guests come and go for many years, knew there were two kinds—those who thought the hotel was a dreadful old barn of a place and those who thought it charming and quaint, so quiet and restful.

“Of course we will be comfortable,” said Mr. Gridley, dropping some coins into Matt’s hand for carrying the bags.

“But this big old hotel is positively spooky.” Mrs. Gridley made one last protest. “It is probably full of mice.”

Matt opened the window wide. “Mice? Oh no, ma’am. The management wouldn’t stand for mice.”

“I wouldn’t mind a few mice,” the boy said, as he looked around the room at the high ceiling, the knotty pine walls, the carpet so threadbare that many of its roses had almost entirely faded, the one chair with the antimacassar on its back, the washbasin and towel racks in the corner of the room. “I like it here,” he announced. “A whole room to myself. Usually I just get a cot in the corner of a motel room.”

His mother smiled, relenting. Then she turned to Matt. “I’m sorry. It’s just that it was so hot crossing Nevada and we are not used to mountain driving. Back on the highway the traffic was bumper to bumper. I’m sure we shall be very comfortable.”

After Matt had gone, closing the door behind him, Mr. Gridley said, “I need a rest before dinner. Four hundred miles of driving and that mountain traffic! It was too much.”

“And if we are going to stay for a weekend I had better unpack,” said Mrs. Gridley. “At least I’ll have a chance to do some drip-drying.”

Alone in Room 215 and unaware that he was being watched, the boy began to explore. He got down on his hands and knees and looked under the bed. He leaned out the open window as far as he could and greedily inhaled deep breaths of pine-scented air. He turned the hot and cold water on and off in the washbasin and slipped one of the small bars of paper-wrapped soap into his pocket. Under the window he discovered a knothole in the pine wall down by the floor and, squatting, poked his finger into the hole. When he felt nothing inside he lost interest.

Next Keith opened his suitcase and took out an apple and several small cars—a sedan, a sports car, and an ambulance about six inches long, and a red motorcycle half the length of the cars—which he dropped on the striped bedspread before he bit into the apple. He ate the apple noisily in big chomping bites, and then laid the core on the bedside table between the lamp and the telephone.

Keith began to play, running his cars up and down the bedspread, pretending that the stripes on the spread were highways and making noises with his mouth—vroom vroom for the sports car, wh-e-e wh-e-e for the ambulance, and pb-pb-b-b-b for the motorcycle, up and down the stripes.

Once Keith stopped suddenly and looked quickly around the room as if he expected to see something or someone, but when he saw nothing unusual he returned to his cars. Vroom vroom. Bang! Crash! The sports car hit the sedan and rolled over off the highway stripe. Pb-pb-b-b-b. The motorcycle came roaring to the scene of the crash.

“Keith,” his mother called from the next room. “Time to get washed for dinner.”

“OK.” Keith parked his cars in a straight line on the bedside table beside the telephone, where they looked like a row of real cars only much, much smaller.

The first thing Mrs. Gridley noticed when she and Mr. Gridley came into the room was the apple core on the table. She dropped it with a thunk into the metal wastebasket beside the table as she gave several quick little sniffs of the air and said, looking perplexed, “I don’t care what the bellboy said. I’m sure this hotel has mice.”

“I hope so,” muttered Keith.

2

The Motorcycle

Except for one terrifying moment when the boy had poked his finger through the mousehole, a hungry young mouse named Ralph eagerly watched everything that went on in Room 215. At first he was disappointed at the size of the boy who was to occupy the room. A little child, preferably two or even three children, would have been better. Little messy children were always considerate about leaving crumbs on the carpet. Oh well, at least these people did not have a dog. If there was one thing Ralph disliked, it was a snoopy dog.

Next Ralph felt hopeful. Medium-sized boys could almost always be counted on to leave a sticky candy bar wrapper on the floor or a bag of peanuts on the bedside table, where Ralph could reach them by climbing up the telephone cord. With a boy this size, the food, though not apt to be plentiful, was almost sure to

be of good quality.

The third emotion felt by Ralph was joy when the boy laid the apple core by the telephone. This was followed by despair when the mother dropped the core into the metal wastebasket. Ralph knew that anything at the bottom of a metal wastebasket was lost to a mouse forever.

A mouse lives not by crumbs alone and so Ralph experienced still another emotion; this time food was not the cause of it. Ralph was eager, excited, curious, and impatient all at once. The emotion was so strong it made him forget his empty stomach. It was caused by those little cars, especially that motorcycle and the pb-pb-b-b-b sound the boy made. That sound seemed to satisfy something within Ralph, as if he had been waiting all his life to hear it.

Pb-pb-b-b-b went the boy. To the mouse the sound spoke of highways and speed, of distance and danger, and whiskers blown back by the wind.

The instant the family left the room to go to dinner, Ralph scurried out of the mousehole and across the threadbare carpet to the telephone cord, which came out of a hole in the floor beside the bedside table.

“Ralph!” scolded his mother from the mousehole. “You stay away from that telephone cord!” Ralph’s mother was a great worrier. She worried because their hotel was old and run-down and because so many rooms were often empty with no careless guests to leave crumbs behind for mice. She worried about the rumor that their hotel was to be torn down when the new highway came through. She worried about her children finding aspirin tablets. Ralph’s father had tried to carry an aspirin tablet in his cheek pouch, the aspirin had dissolved with unexpected suddenness, and Ralph’s father had been poisoned. Since then no member of the family would think of touching an aspirin tablet, but this did not prevent Ralph’s mother from worrying.

Most of all Ralph’s mother worried about Ralph. She worried because he was a reckless mouse, who stayed out late in the daytime when he should have been home safe in bed. She worried when Ralph climbed the curtain to sit on the windowsill to watch the chipmunk in the pine tree outside and the cars in the parking lot below. She worried because Ralph wanted to go exploring down the hall instead of traveling under the floorboards like a sensible mouse. Heaven only knew what dangers he might meet in the hall—maids, bellboys, perhaps even cats. Or what was worse, vacuum cleaners. Ralph’s mother had a horror of vacuum cleaners.

Ralph, who was used to his mother’s worries, got a good running start and was already halfway up the telephone cord.

“Remember your Uncle Victor!” his mother called after him.

Ralph seemed not to hear. He climbed the cord up to the telephone, jumped down, and ran around to the row of cars. There it was on the end—the motorcycle! Ralph stared at it and then walked over and kicked a tire. Close up the motorcycle looked even better than he expected. It was new and shiny and had a good set of tires. Ralph walked all the way around it, examining the pair of chromium mufflers and the engine and the hand clutch. It even had a little license plate so it would be legal to ride it.

“Boy!” said Ralph to himself, his whiskers quivering with excitement. “Boy, oh, boy!” Feeling that this was an important moment in his life, he took hold of the handgrips. They felt good and solid beneath his paws. Yes, this motorcycle was a good machine all right. He could tell by the feel. Ralph threw a leg over the motorcycle and sat jauntily on the plastic seat. He even bounced up and down. The seat was curved just right to fit a mouse.

But how to start the motorcycle? Ralph did not know. And even if he did know how to start it, he could not do much riding up here on the bedside table. He considered pushing the motorcycle off onto the floor, but he did not want to risk damaging such a valuable machine.

Ralph bounced up and down on the seat a couple more times and looked around for some way to start the motorcycle. He pulled at a lever or two but nothing happened. Then a terrible thought spoiled his pleasure. This was only a toy. It would not run at all.

Ralph, who had watched many children in Room 215, had picked up a lot of information about toys. He had seen a boy from Cedar Rapids throw his model airplane on the floor because he could not make its plastic parts fit properly. A little girl had burst into tears and run sobbing to her mother when her doll’s arm had come out of its socket. And then there was that nice boy, the potato chip nibbler, who stamped his foot because the batteries kept falling out of his car.

But this toy could not be like all those other toys he had seen. It looked too perfect with its wire spokes in its wheels and its pair of shiny chromium exhaust pipes. It would not be right if it did not run. It would not be fair. A motorcycle that looked as real as this one had to run. The secret of making it run must be perfectly simple if only Ralph had someone to show him what it was.

Ralph was not satisfied just sitting on the motorcycle. Ralph craved action. After all, what was a motorcycle for if it wasn’t action? Who needed motorcycle riding lessons? Not Ralph! He tried pushing himself along with his feet. This was not nearly fast enough, but it was better than nothing. He moved his feet faster along the tabletop and then lifted them up while he coasted. Feeling braver, he bent low over the handlebars and worked his feet still faster toward the edge of the bedside table. When he worked up a little speed he would coast around the corner. He scrabbled his feet on the tabletop to gain momentum. In a split second he would steer to the left—

At that moment the bell on the telephone rang half a ring, so close that it seemed to pierce the middle of Ralph’s bones. It rang just that half ring, as if the girl at the switchboard realized she had rung the wrong room and had jerked out the cord before the ring was finished.

That half a ring was enough. It shattered Ralph’s nerves and terrified him so that he forgot all about steering. It jumbled his thoughts until he forgot to drag his heels for brakes. He was so terrified he let go of the handgrips. The momentum of the motorcycle carried him forward, over the edge of the table. Down, down through space tumbled Ralph with the motorcycle. He tried to straighten out, to turn the fall into a leap, but the motorcycle got in his way. He grabbed in vain at the air with both paws. There was nothing to clutch, nothing to save him, only the empty air. For a fleeting instant he thought of his poor old Uncle Victor. That was the instant the motorcycle landed with a crash in the metal wastebasket.

Ralph fell in a heap beside the motorcycle and lay still.

3

Trapped!

Even though Ralph woke up feeling sick and dizzy, his first thought was of the motorcycle. He hoped it was not broken. He sat there at the bottom of the wastebasket until the whirly feeling in his head stopped and he was able, slowly and carefully, to stand up. He stretched each aching muscle and felt each of his four legs to make certain it was not broken.

When Ralph was sure that he was battered but intact he examined the motorcycle. He set it upright and rolled it backward and forward to make sure the wheels still worked. One handlebar was bent and some of the paint was chipped off the rear fender, but everything else seemed all right. Ralph hoped so, but there was no way he could find out until he figured out how to start the engine. Now he ached too much even to try.

Wearily Ralph dragged himself over to the wall of his metal prison and sat down beside the apple core to rest his aching body. He leaned back against the side of the wastepaper basket, closed his eyes, and thought about his Uncle Victor. Poor nearsighted Uncle Victor. He, too, had landed in a metal wastepaper basket, jumping there quite by mistake. Unable to climb the sides, he had been trapped until the maid came and emptied him out with the trash. No one knew for sure what had happened to Uncle Victor, but it was known that trash in the hotel was emptied into an incinerator.

Ralph felt sad and remorseful thinking about his Uncle Victor getting dumped out with the trash. His mother had been right after all. His poor mother, gathering crumbs for his little brothers and sisters while he, selfish mouse that he was, sat trapped in a metal prison from which the only escape was to be thrown away like an old gum wrapper.

Ralph thought sadly of his comfortable home i

n the mousehole. It was a good home, untidy but comfortable. The children who stayed in Room 215 usually left a good supply of crumbs behind, and there was always water from the shirts hung to drip-dry beside the washbasin. It should have been enough. He should have been content to stay home without venturing out into the world looking for speed and excitement.

Outside in the hall Ralph heard footsteps and Matt, the bellboy, saying, “These new people in 215 and 216, somehow they got the idea there are mice in the hotel. I just opened the window and told them the management wouldn’t stand for it.”

Ralph heard a delighted laugh from the second-floor maid, a college girl who was working for the summer season. “Mice are adorable but just the same, I hope I never find any in my rooms. I’m afraid of them.” There were two kinds of employees at the Mountain View Inn—the regulars, none of them young, and the summer help, who were college students working during the tourist season.

“If you don’t like mice you better stay away from that knothole under the window in Room 215,” advised Matt.

The sound of voices so close made Ralph more eager than ever to escape. “No!” he shouted, his voice echoing in the metal chamber. “I won’t have it! I’m too young to be dumped out with the trash!”

In spite of his aches he jumped to his feet, ran across the wastebasket floor, and leaped against the wall, only to fall back in a sorry heap. He rose, backed off, and tried again. There he was on the floor of the wastebasket a second time. It was useless, utterly useless. He did not have the strength to tip over the wastebasket.

Ramona Quimby, Age 8

Ramona Quimby, Age 8 Dear Mr. Henshaw

Dear Mr. Henshaw Beezus and Ramona

Beezus and Ramona A Girl from Yamhill

A Girl from Yamhill Ramona Forever

Ramona Forever Jean and Johnny

Jean and Johnny The Luckiest Girl

The Luckiest Girl Emily's Runaway Imagination

Emily's Runaway Imagination Ribsy

Ribsy Ramona the Pest

Ramona the Pest Socks

Socks Ramona's World

Ramona's World Strider

Strider The Mouse and the Motorcycle

The Mouse and the Motorcycle Henry and the Paper Route

Henry and the Paper Route Ramona the Brave

Ramona the Brave Henry Huggins

Henry Huggins Ramona and Her Mother

Ramona and Her Mother Ralph S. Mouse

Ralph S. Mouse Sister of the Bride

Sister of the Bride Henry and the Clubhouse

Henry and the Clubhouse Muggie Maggie

Muggie Maggie Runaway Ralph

Runaway Ralph Ramona and Her Father

Ramona and Her Father Henry and Ribsy

Henry and Ribsy Henry and Beezus

Henry and Beezus Two Times the Fun

Two Times the Fun Fifteen

Fifteen Mitch and Amy

Mitch and Amy