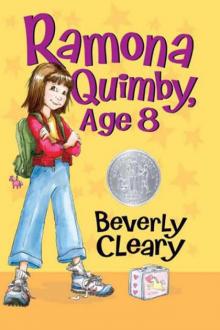

Ramona Quimby, Age 8

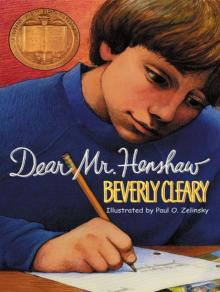

Ramona Quimby, Age 8 Dear Mr. Henshaw

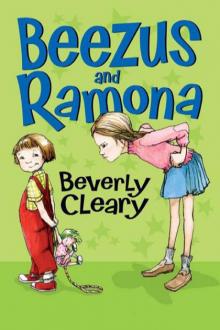

Dear Mr. Henshaw Beezus and Ramona

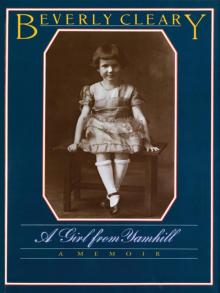

Beezus and Ramona A Girl from Yamhill

A Girl from Yamhill Ramona Forever

Ramona Forever Jean and Johnny

Jean and Johnny The Luckiest Girl

The Luckiest Girl Emily's Runaway Imagination

Emily's Runaway Imagination Ribsy

Ribsy Ramona the Pest

Ramona the Pest Socks

Socks Ramona's World

Ramona's World Strider

Strider The Mouse and the Motorcycle

The Mouse and the Motorcycle Henry and the Paper Route

Henry and the Paper Route Ramona the Brave

Ramona the Brave Henry Huggins

Henry Huggins Ramona and Her Mother

Ramona and Her Mother Ralph S. Mouse

Ralph S. Mouse Sister of the Bride

Sister of the Bride Henry and the Clubhouse

Henry and the Clubhouse Muggie Maggie

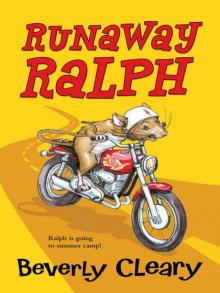

Muggie Maggie Runaway Ralph

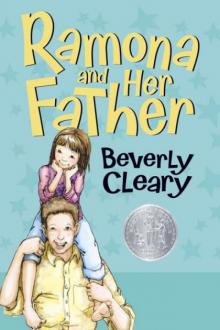

Runaway Ralph Ramona and Her Father

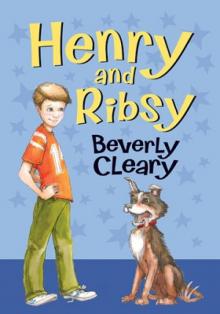

Ramona and Her Father Henry and Ribsy

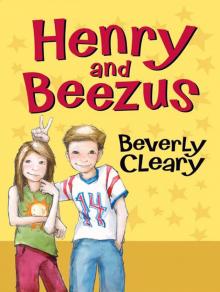

Henry and Ribsy Henry and Beezus

Henry and Beezus Two Times the Fun

Two Times the Fun Fifteen

Fifteen Mitch and Amy

Mitch and Amy