- Home

- Beverly Cleary

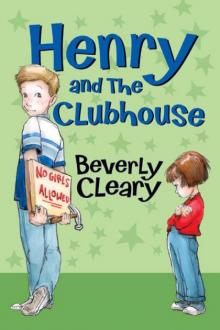

Henry and the Clubhouse Page 2

Henry and the Clubhouse Read online

Page 2

“He just laughed and wanted to know if I was taking over your route,” answered Mrs. Huggins.

Henry wished he had his bicycle. He could actually cover his route almost as fast on foot, but it was more fun to deliver papers on his bicycle. Because he was short for his age the bag of papers bumped against his legs when he went on foot. He walked up one driveway and down the next, remembering which customer wanted his paper left on the doormat and which one had warned him against breaking the geraniums in the flower box on the porch.

Henry walked as fast as he could and soon covered his route. He was late, he knew, but with luck no one would complain—and so far he had been lucky. There was no reason why he should not continue to be. He was tired and sweaty when he reached home, but he was cheerful. The papers were delivered, weren’t they? That was all that mattered.

When Henry opened the front door he was surprised to see his father wearing a white shirt and a necktie. Mr. Huggins always wore a sport shirt around home. “Hi, Dad. How come you’re all dressed up?” he asked.

“Because your mother had quite a day with one thing or another around here, and we are going to take her out to dinner for a change,” said Mr. Huggins.

“Oh—maybe I had better get cleaned up.” Henry was surprised at this change in routine. He hoped they would not go to a fancy place with cloth napkins and a long menu. When he went out to dinner he liked to order a hamburger and pie.

“Well, Henry!” Mr. Huggins sounded stern. “Don’t you have anything to say for yourself?”

“Why…uh…I finally got the papers delivered,” answered Henry, not quite certain what his father expected of him.

“It seems to me your mother also delivered quite a few papers,” said Mr. Huggins.

“Yeah, and golly, Dad, you should see her throw,” confided Henry, demonstrating to his father the way his mother delivered papers. “It is pretty awful.”

“Henry, I want one thing clearly understood,” said Mr. Huggins, ignoring his son’s remark. “That paper route is yours. It is not your mother’s route and it is not my route. You are to deliver the papers and collect the money and do all the work yourself, and if you can’t do it without any help from us, you will have to give the route to someone else. Do you understand?”

Henry looked at the carpet. His father did not often speak to him this way, and he felt terrible. He wanted his father to be proud of him because he was the youngest paper carrier in the neighborhood. “Yes, Dad,” he answered. He felt he should offer some explanation for forgetting his route. “I was planning to get some old boards to build a doghouse.”

Mr. Huggins grinned. “You don’t need to build a doghouse. You’re in a doghouse with your mother already.”

Mrs. Huggins came clicking into the room on high heels. Henry caught a whiff of perfume and noticed she was wearing one of her best dresses, which meant a restaurant with cloth napkins. She looked so nice Henry felt ashamed of himself for criticizing the way she threw and for wanting a hamburger for dinner. “Gee, Mom, I’m sorry I caused you so much trouble,” he said. “It just seemed like such a good chance to go for a ride in a bathtub that I just—well, I forgot all about my route.”

“In a bathtub!” exclaimed Mrs. Huggins.

“Sure. Didn’t you know? Mr. Grumbie had this old bathtub he was hauling to the dump on a trailer.”

“A bathtub! I had no idea—” Mrs. Huggins sat down and began to laugh. “You mean you were riding down Lombard Street in a bathtub?”

“You told me to find something to do,” Henry pointed out.

“Yes, I know I did,” admitted Mrs. Huggins, “but riding around town in a bathtub wasn’t exactly what I had in mind. Honestly, Henry, sometimes I wonder how you get into these things.”

“I don’t know, Mom, I just do,” said Henry thinking with regret of the good idea that had somehow gone wrong. He knew one thing for sure. If he was going to keep his paper route he had better not get into things. He had better keep out of things—especially late in the afternoon.

2

Henry and The New Dog

Henry soon found that there was not enough wood in a bathtub crate to build a really good doghouse. As he rode around the neighborhood delivering papers, he kept his eye out for any old boxes or packing cases that he could use. There was one empty house in the neighborhood which he passed every day hoping he would get some packing cases from the new owners, but the house remained empty. Wood was so scarce that he was about to give up the idea of a house for Ribsy when he had an unexpected piece of luck.

Most of the houses in Henry’s neighborhood had been built way back in the nineteen-twenties when cars were shorter and narrower than they are today. Now many people were finding their new cars too long for their old garages and so they built boxlike additions onto the ends of their garages to make them long enough for their cars.

One neighbor, Mr. Bingham, was not so fortunate. When he proudly drove his new car into his garage he found there was no way for him to get out of it. His garage was so narrow he could not open the door of his car. So poor Mr. Bingham backed out and parked his car on the driveway. All the neighbors on Klickitat Street had a good laugh over this, and Mr. Bingham announced that he was going to tear down his old garage and build a larger one.

As soon as Mr. Bingham began to tear down the garage, Henry rode his bicycle over to his house to ask if he could have some of the old lumber.

“Sure, Henry, help yourself,” said Mr. Bingham, who was prying at a board with a crowbar. “Take all you want but get it out of here before Saturday, when the truck comes to haul it away.”

“OK, Mr. Bingham,” agreed Henry. “Do you want to get rid of the windows, too?”

“Take anything you want,” said Mr. Bingham.

Doghouse! Why, there would be enough lumber for a clubhouse, a clubhouse with windows and a good one, too. He would save up his paper-route money and buy one of those down-filled sleeping bags he had seen in the window of the sporting goods store and sleep out in the clubhouse he would build out of all the secondhand lumber.

Now Henry found himself with more to do than he had time for. He could not neglect his paper route, so he saw that he would have to have help. He told his friends Robert and Murph about the free lumber and they saw the point at once.

“Sure, we’ll help,” they both said. The boys borrowed wagons and every afternoon between school and paper-route time they hauled lumber from Mr. Bingham’s driveway to the Hugginses’ backyard. When Henry left to fold his papers, Robert and Murph went on hauling. By Saturday the boys were sure they had enough lumber for a clubhouse.

“Let’s start building,” said Henry eagerly.

“Nope,” said Murph. “When you build a house, you’ve got to have a plan. You can’t build it any old way.”

“Aw, Murph,” said Robert. “Where are we going to get a plan?”

Henry, too, was skeptical. He thought that any old way was the only way to build a clubhouse. “Yes, where are we going to get a plan?”

“I can draw one,” said Murph. “I’ll do it this weekend. But remember, when we get the clubhouse built, no girls allowed.”

“No girls allowed,” vowed Henry and Robert.

“And when we get it built, we can sleep in it in our sleeping bags,” added Henry, thinking to himself, when I get a sleeping bag. The boys agreed this was the thing to do with a clubhouse.

Mrs. Huggins looked at the old lumber in her yard and said, “My goodness, Henry, isn’t that a lot of lumber?”

“Don’t worry, Mom,” Henry assured her. “The clubhouse will be real neat when we get it finished and I’ll saw up the leftover boards for kindling.”

Mr. Huggins looked at the old lumber. “I don’t know about this, Henry. It looks to me as if you have taken on a pretty big job.”

“The three of us can do it, Dad,” said Henry, eager for his father’s approval. “And I won’t let it interfere with my paper route. Cross my heart.”

“See that you don’t,” said Mr. Huggins. “If you can’t handle them both you’ll either have to give up your route or tear down the clubhouse.”

That weekend Murph, who was the smartest boy in the whole school and practically a genius, did draw a plan. He drew it on squared paper, each square equaling one foot. Henry was pretty impressed when he saw it and realized that Murph had been right. It would not do to build a clubhouse any old way.

Murph would not hear of building the clubhouse directly on the ground. “We don’t want termites eating our clubhouse,” he said.

Henry agreed that it would not do to have bugs chewing away at their clubhouse. This meant the boys had to buy some Kwik-Mix concrete and make four cement blocks for their clubhouse to rest on. It was soon plain to Henry that there was more to building a clubhouse than he had realized and that it was going to take a lot of time—time that he was not sure he had to spare because of his paper route. However, he could not back out now that Robert and Murph had already worked so hard on their new project.

Then one afternoon when Henry was folding his Journals on Mr. Capper’s driveway with the other paper carriers, Scooter McCarthy spoke. “Say, Mr. Capper, I will be needing one more paper after this,” he said.

“Is that so?” Mr. Capper sounded interested. “A new subscriber?”

“That’s right, Mr. Capper.” Scooter quite plainly was pleased with himself for having sold a subscription.

Henry suddenly pretended to be interested in a headline in the paper he was folding, because he hoped that if he did not look at Mr. Capper, Mr. Capper might not look at him. Henry was ashamed, because it was already October and he had not sold a single Journal subscription. Not that he hadn’t tried—a little bit. He really had rung several strange doorbells before he became interested in the clubhouse, and had tried to sell subscriptions, but the results were discouraging. Strangers had a way of listening to his sales talk about the Journal’s easy-to-read type with amused smiles and then saying, “No thank you.” One man interrupted with a brusque “Not today” and closed the door in Henry’s face. A lady embarrassed him by telling him what a splendid little salesman he was and then saying she couldn’t afford to take another paper. Splendid little salesman! That was the last straw. After that Henry found it easy to think up excuses for not trying to sell new subscriptions.

Now Mr. Capper was saying, “Good for you, Scooter. Suppose you tell us how you went about selling the subscription.”

“Aw, it was easy,” boasted Scooter, stuffing his folded papers into his canvas bag. “I just told this man what a good paper the Journal was and he said he didn’t have time to read it, because he went fishing every Sunday and I said, ‘You could use it to wrap your fish eggs in,’ and he laughed and said OK, put him down for a subscription, so I did.”

“I call that quick thinking on your part, Scooter,” said Mr. Capper. “The rest of the boys could take a lesson from you.”

Out of the corner of his eye Henry could see Mr. Capper looking around the group of boys. “What about you, Henry?” asked Mr. Capper. “You haven’t turned in any subscriptions since you have had your route.”

“Well…I—I have been trying,” Henry said, admitting to himself that he really had not tried very hard. He had been much too busy with the clubhouse.

“I know it’s hard to get started sometimes,” said Mr. Capper sympathetically. “I’ll tell you what you do. The other day I saw a Sold sign on a house on your route. When the new owners move in, you march right up to that front door, ring the doorbell, and sell them a subscription to the paper.”

“Yes, sir.” Mr. Capper made it sound so easy—march right up and sell them a subscription, just like that. “I’ll try, Mr. Capper,” said Henry, who knew the house the district manager was referring to. It was the house where he had once hoped to get enough old boxes to build a doghouse. It seemed a long time ago.

And so each day, as Henry delivered his papers, he watched for the new owners to move into the empty house. When he finally did see packing crates and empty cartons stacked on the driveway he decided he should give the people a little time, say about a week, to get settled before he marched right up and rang that doorbell.

The next afternoon Mr. Capper said, “Well, Henry, I see the new owners have moved into the empty house.”

“I am going over today as soon as I finish my route,” promised Henry, knowing he could not put off the task any longer.

When Henry had delivered his last paper he hung his canvas bag in the garage, washed his hands, combed his hair, and, followed by Ribsy, walked the two blocks to call on the new neighbors. He did not ride his bicycle, because it seemed more businesslike to go on foot. Fuller Brush men did not ride bicycles.

As he approached the house he whispered to himself some of the things he planned to say. “Good afternoon. I am Henry Huggins, your Journal newsboy. I deliver the Journal to a lot of your neighbors.” That much he was sure of, but he did not know what to say next. Find a selling point, Mr. Capper always said. Talk about some part of the paper that would interest a new subscriber.

Henry walked more and more slowly. Ribsy finally had to sit down and wait for him to catch up. The Journal had a good sports section…a good church section…. How was Henry supposed to know what would interest a new subscriber? What if he told someone about the church section when all he wanted was to read the funny papers?

But before Henry could decide what to say, he met Beezus and her little sister Ramona. Ramona was wearing a loop of string around her neck. The ends of the string were fastened with Scotch tape to a cardboard tube.

“Hi,” said Henry to Beezus. “What are you doing?”

“Keeping Ramona away from the television set,” answered Beezus. “Mother says she spends too much time in front of it.”

“Ask me my name,” Ramona ordered Henry.

Henry could feel no enthusiasm at all for this new game of Ramona’s. “What’s your name?” he asked in a bored voice rather than risk Ramona’s having a tantrum because he would not play.

Ramona held the paper tube in front of her mouth. “My name is Danny Fitzsimmons,” she answered, looking down at the sidewalk and smiling in a self-conscious way that was not at all like Ramona.

“It is not,” contradicted Henry. “You aren’t even a boy.”

“She’s just pretending she’s being interviewed on the Sheriff Bud program,” explained Beezus. “That’s her microphone she’s holding.”

“Oh,” was all Henry could find to say.

“My name is Danny Fitzsimmons,” repeated Ramona, smiling shyly in an un-Ramona-like way, “and I want to say hello to my mommy and my daddy and my sister Vicki, who is having a birthday, and Mrs. Richards, who is my kindergarten teacher, and Lisa Kelly, who is my best friend, and Gloria Lofton, whose cat just had kittens and she might give me one, and her dog Skipper and all the boys and girls in my kindergarten class and all the boys and girls at Glenwood Primary School and Georgie Bacon’s sister Angela, but I won’t say hello to Georgie, because I don’t like him, and…”

“Oh, for Pete’s sake.” Henry was disgusted with Ramona’s new game. “Why don’t you just say hello to the whole world and be done with it?” He had no time for this sort of thing. He was on his way to sell a Journal subscription and get back to the clubhouse. “So long, Beezus,” he said.

“…and Bobby Brogden who has a loose tooth…” Ramona was saying as Henry went on down the street.

When Henry came to the house that was his destination, he turned to Ribsy and said, “Sit,” not because he expected Ribsy to sit, but because he wanted to put off ringing that doorbell a little longer. He had not decided what to use as a selling point, because he could not even guess what might interest a new neighbor.

Ribsy sat a moment and then got up and sniffed at the shrubbery.

“I said ‘Sit,’” Henry told his dog, deciding that it would be a good idea if Ribsy really did sit. Some people were very particular about dogs ru

nning through their flowers and he was anxious to make a good impression.

Like the good dog he was, part of the time, Ribsy sat once more, but he did not stay seated. He stood up and wagged his tail.

“Sit!” ordered Henry sternly, as he started up the steps.

Ribsy appeared to think it over.

“Sit!” Henry raised his voice.

Ribsy waved his tail as if to say, Do I really have to?

A strange dog, a Dalmatian, came trotting around the house and began to investigate Ribsy. The dogs sidled around each other, sniffing. Henry did not pay much attention. Dogs who were strangers to each other always did this.

Next a woman who was wearing an apron, and had a smudge of dust on her cheek, appeared on the driveway at the side of the house. She was older than Henry’s mother. Probably she was old enough to be a grandmother. Before Henry had a chance to speak, the Dalmatian left Ribsy and frolicked over to his owner. Ribsy, an agreeable dog who was ready to play, followed.

That was Ribsy’s mistake. Now he was trespassing on the Dalmatian’s territory. The Dalmatian began to growl deep in his throat and to hold his whiplike tail stiff and straight.

Ribsy stopped short. This was his neighborhood. He was here first. It was the Dalmatian who was trespassing. Each dog began to resent the other’s looks, sound, and smell.

“Ribsy!” Henry spoke sharply.

“Ranger!” The woman spoke sharply, too.

The dogs paid no attention to their owners. Each was too intent on letting the other know exactly what he thought of him. The growls grew louder and deeper and they raised their lips and bared their teeth as if they were sneering at each other. And just who do you think you are? Ribsy’s growl seemed to say.

I have just as much right here as you have, Ranger’s growl answered.

No, you don’t, said Ribsy. I was here first.

I’m bigger, growled Ranger.

You’re a bully, growled Ribsy.

Get off my property, Ranger told Ribsy.

Ramona Quimby, Age 8

Ramona Quimby, Age 8 Dear Mr. Henshaw

Dear Mr. Henshaw Beezus and Ramona

Beezus and Ramona A Girl from Yamhill

A Girl from Yamhill Ramona Forever

Ramona Forever Jean and Johnny

Jean and Johnny The Luckiest Girl

The Luckiest Girl Emily's Runaway Imagination

Emily's Runaway Imagination Ribsy

Ribsy Ramona the Pest

Ramona the Pest Socks

Socks Ramona's World

Ramona's World Strider

Strider The Mouse and the Motorcycle

The Mouse and the Motorcycle Henry and the Paper Route

Henry and the Paper Route Ramona the Brave

Ramona the Brave Henry Huggins

Henry Huggins Ramona and Her Mother

Ramona and Her Mother Ralph S. Mouse

Ralph S. Mouse Sister of the Bride

Sister of the Bride Henry and the Clubhouse

Henry and the Clubhouse Muggie Maggie

Muggie Maggie Runaway Ralph

Runaway Ralph Ramona and Her Father

Ramona and Her Father Henry and Ribsy

Henry and Ribsy Henry and Beezus

Henry and Beezus Two Times the Fun

Two Times the Fun Fifteen

Fifteen Mitch and Amy

Mitch and Amy