- Home

- Beverly Cleary

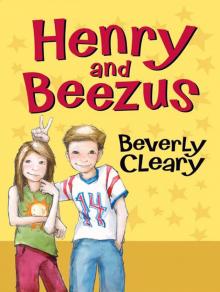

Henry and Beezus Page 5

Henry and Beezus Read online

Page 5

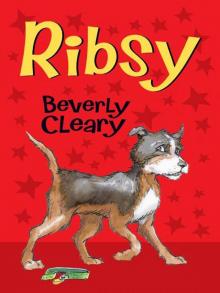

“It works!” shouted Henry. “It really works! I’m going to get Ribsy untrained after all.” He ran into the house again and filled his army-surplus canteen with water, in case he needed to reload his pistol.

Beezus and Robert had the papers rolled and stuffed into the canvas bag, which Henry now lifted over his head. The Journals were heavier than he expected. “Come on,” he said. “Let’s go.”

By then Beezus had succeeded in getting the water pistol away from Ramona. “I’ll help you keep Ribsy covered,” she said.

Henry threw a Journal onto the lawn of the first house on the list. Ribsy bounded after the paper, but the minute he opened his mouth to pick it up, Henry and Beezus shot him with two streams of water. Looking surprised and unhappy, Ribsy backed away from the paper and shook himself. The next time Henry threw a paper, Ribsy approached it cautiously. The instant he touched it, Beezus and Henry opened fire. This time Beezus shot from the hip.

“You’re dead!” shrieked Ramona. Ribsy decided he wasn’t interested in the paper after all.

The third time Henry threw a paper, Ribsy ignored it. He was too busy sniffing a bush even to look at it.

“Good dog,” said Henry, bending over to pet him. The weight of the papers in the canvas bag nearly tipped him over.

Ribsy wagged his tail. “Good old Ribsy,” said Henry proudly. Ribsy was untrained at last.

When the children returned after delivering all the papers without a single mistake, they found Scooter waiting on the front steps. “How many did your mutt run off with?” he wanted to know.

“He isn’t a mutt and he didn’t run off with any,” boasted Henry. “He wouldn’t touch a paper. See?” Henry tossed his own copy of the Journal onto the grass. Ribsy looked the other way.

“I guess I did a pretty good job of delivering papers,” bragged Henry. “You won’t get any complaints tonight.”

“That’s right,” agreed Beezus. “I checked every address on the list with him just to make sure.”

Scooter threw one leg over his bicycle.

“And I get to deliver papers while you’re away, don’t I?” Henry was thinking of his bike fund again, now that Ribsy was untrained.

“Sure,” said Scooter, “if you don’t think it’s too hard work for a kid without a bike.”

“You just wait,” said Henry. “I bet I get that bike sooner than you think.”

“Ha,” said Scooter, pedaling down the street.

“You’re dead!” shrieked Ramona, squirting her pistol with deadly accuracy.

4

Henry Parks His Dog

One Friday after school Henry was fixing himself a snack of bread, peanut butter, and strawberry jam when the doorbell rang.

“Come in, Beezus,” he heard his mother say.

As Henry went into the living room, he held up his bread and licked the jam that had run down his wrist. Beezus and her little sister Ramona each held a gnawed cabbage core. They had stopped eating because they were too polite to eat in front of people.

Beezus handed Henry a newspaper clipping. “I thought maybe you’d like to see this.”

“Bikes for Tykes,” was the headline. “Lost Bicycles up for Sale Tomorrow.”

“Hey, maybe you’ve got something.” Henry read faster.

“Enough bicycles—some hundred or more—have been found by the police this past year to equip half a company of soldiers, and tomorrow at ten A.M. they go up for auction at the Glenwood police station.”

This was Henry’s chance. “Hey, Mom, look! Isn’t an auction where somebody holds up something and everybody says how much he’ll pay for it and the one who says the most gets it?”

“Yes, it is,” answered Mrs. Huggins, as she read the clipping.

“Boy! I’ve got four dollars and fourteen cents saved. I bet I can get a bike for that much.” Henry pictured a hundred soldiers riding by on bicycles—and one of those bicycles was meant for him. He’d show old Scooter yet.

Mrs. Huggins looked doubtful. “I wouldn’t be too sure,” she advised. “After all, there must be some reason why the bicycles haven’t been claimed. If you lost a bicycle you’d try to get it back, wouldn’t you?”

“Yes,” agreed Henry, who was sure most of the bicycles belonged to rich boys who had so many bikes they didn’t miss one when they lost it. “But I can go, can’t I, Mom?”

“Yes, it won’t hurt to try,” said Mrs. Huggins, “but don’t be too disappointed if you don’t get a bicycle.”

“And I can go with you, can’t I?” asked Beezus eagerly.

“Well…” Henry didn’t want to bother with Beezus. He wanted to go early and look the bicycles over. If he could get a good one, he would ride it in the Rose Festival parade in a couple of weeks and really show it off.

“Of course you may go, Beezus,” said Mrs. Huggins. “Henry will be glad to take you.”

“Isn’t it pretty far for Ramona to walk?” asked Henry. “It’s about ten blocks. Long blocks, too.”

“Oh, no. Ramona never gets tired,” said Beezus. “Daddy says he wishes sometimes she would, but she never does. Come on, Ramona. See you in the morning, Henry.” Gnawing on their cabbage cores, the girls left.

“Aw, Mom,” said Henry, “why did you have to go and say they could come with me? I don’t want to drag a couple of girls around all morning.”

“Now, Henry,” said his mother firmly, “Beezus was nice enough to come and tell you about the auction, and it won’t hurt you to let her go with you.”

“Oh, all right,” muttered Henry.

“Why, Henry, you and Beezus used to play together so nicely. Don’t you like her any more?”

“She’s all right, I guess. She’s just a girl, is all,” said Henry, thinking of the shiny red bicycle he was going to buy the next day. Maybe Beezus would forget to come.

But Beezus did not forget. The next morning after breakfast Henry found the two girls sitting on the front steps waiting for him. When Henry and Ribsy came out of the house, Beezus started down the walk. Ramona stood still until Beezus went back and made a winding motion behind her little sister. Then Ramona walked along beside her.

“She’s pretending she has to be wound up like a toy before she can walk, and I forgot to wind her,” explained Beezus.

Henry groaned. Girls thought of the dumbest things. He tried to keep ahead of them so people wouldn’t think they were walking together. Ribsy trotted beside him.

“Henry Huggins, you wait for us!” said Beezus. “Your mother said we could go with you and if you don’t wait I’ll tell on you.”

“Well, come on then,” answered Henry crossly, anxious for a glimpse of that red bicycle before anyone else got there.

Suddenly Ramona stopped. Beezus wound her up again and they went on. “She ran down,” explained Beezus.

Girls! Henry was disgusted. It seemed to him that it had taken half the morning to go three blocks. He saw a couple of other boys walking in the same direction, and he wondered if they were going to the auction, too. He began to walk faster.

Then Henry saw Mrs. Wisser, a friend of his mother’s, coming toward him. The sight of three more boys coming along on the other side of the street made Henry hope she wouldn’t stop him long.

“Well, if it isn’t Henry Huggins,” she exclaimed. “And Beatrice.”

“Hello, Mrs. Wisser,” said Henry and Beezus politely.

“My, Henry, how you have grown! And you’re getting to look more like your father every day. I was telling your mother only yesterday that every time I see you, you look more like your father.”

Another boy hurried down the street. Was every boy in town going to the auction? Henry smiled as politely as he could at Mrs. Wisser and looked uneasily in the direction of the police station. The best bikes would be gone, he was sure, by the time he got there. Maybe he could find an older bike that just needed a little paint or something. He had plenty of time before the parade to fix it up. He tried not to show how impatient he felt.

/>

“Don’t you think he looks more like his father every day?” asked Mrs. Wisser of Beezus.

“Yes, I guess he does,” said Beezus. She had also noticed the boys going in the direction of the police station, but she felt she should say something. “Especially the way his hair sticks up,” she added.

Henry gave her a disgusted look.

“And is this Ribsy?” asked Mrs. Wisser. “Nice doggie.”

Ribsy sat down and scratched. Thump, thump, thump went his hind leg on the sidewalk.

“And this must be Ramona. How are you, sweetheart?”

Ramona was silent.

“What a pretty dress you’re wearing,” said Mrs. Wisser. “And it has a pocket, too. Do you have something in your pocket?”

“Yes,” said Ramona.

“Isn’t she sweet?” said Mrs. Wisser to Beezus. “What do you have in your little pocket, dear?”

Ramona poked her fist into her pocket and pulled out a fat slimy garden slug, which she held out to Mrs. Wisser.

“Oh,” gasped Mrs. Wisser. “Oh!”

“Ramona, throw that thing away,” ordered Beezus.

Henry couldn’t help grinning, Mrs. Wisser looked so horrified.

“Well…I must be running along,” said Mrs. Wisser.

“Good-bye, Mrs. Wisser,” said Beezus and Henry. Ramona put her slug back in her pocket, Beezus wound her up again, and they went on.

Until they reached the Glenwood shopping district, Henry almost thought girls were good for something after all. Then Ramona stopped in front of the supermarket. “I’m hungry,” she announced.

“Come on, Ramona,” coaxed Beezus. “We’re in a hurry.”

“I’m hungry,” repeated Ramona.

Henry groaned. He knew they couldn’t go any farther until Ramona had something to eat. That was the kind of little girl she was.

“I have a quarter,” said Beezus. “I better get her something.”

“OK,” agreed Henry reluctantly. “I could stand something myself.” Then Henry noticed a sign on the door of the market. It said, “No dogs allowed in food stores.”

“Lie down, Ribsy,” he ordered, as he went through the swinging door.

On the next swing of the door Ribsy came in, too. “Sorry, sonny,” said a clerk. “You’ll have to take your dog outside.”

“Beat it,” said Henry to his dog. Ribsy sat down. “Come on, you old dog,” said Henry, seizing his pet by the collar and dragging him out onto the sidewalk.

Henry hurried back into the market and was trying to decide between a bag of Cheezy Chips and a box of Fig Newtons when the clerk said, “Say, sonny, I thought I told you to get that dog out of here.”

Once more Henry dragged Ribsy out. This time he dug into his pocket and pulled out a piece of heavy twine. He tied one end to Ribsy’s collar and fastened the other end securely to a parking meter. “Now don’t you chew the twine,” he said, before he went back into the store. He chose the Cheezy Chips and stood impatiently behind Beezus in line at the cashier’s counter.

Finally they were out on the sidewalk again, where they found Ribsy busy chewing the twine. Beezus had to stop and find several lions in the animal-cracker box she had bought, because Ramona wanted to eat all the lions first. Henry felt it was pretty useless to try to go any place with a couple of girls. But maybe he would get there in time to find a bike in fairly good condition with just a few spokes missing.

“Hey, Henry!” It was Robert calling.

Henry, who was trying to untie Ribsy from the parking meter, saw Scooter pedaling his bicycle slowly down the sidewalk while Robert jogged along at his side.

“Bet you’re going to the bike sale,” said Scooter. “We’re going just to watch.”

“What’s that paper under Ribsy’s collar?” asked Robert.

“What paper?” said Henry. Sure enough, there was a paper under Ribsy’s collar. Henry pulled it out and unfolded it as the other children crowded around.

Scooter was first to understand. He shouted with laughter. “It’s a parking ticket. Ribsy got a parking ticket!”

The children all laughed. “Don’t be dumb,” said Henry. “Everybody knows dogs don’t get parking tickets.”

“Sure it’s a ticket,” said Scooter. “See, it says ‘Notice of traffic violation’ across the top, and violation means he’s done something wrong, doesn’t it?”

“Did you put a penny in the meter?” asked Robert.

“That’s right. Did you put a penny in the meter when you parked your dog?” laughed Scooter.

“I didn’t know leaving a dog on the sidewalk counted as parking,” said Henry, looking at the meter. “See! The red thing doesn’t show and there’s still sixteen minutes left from whoever put the money in before.”

“Maybe there was a car here and Ribsy got a ticket for double parking,” said Scooter, guffawing again.

Beezus handed Ramona another lion. “That’s all the lions. You’ll have to eat camels now.” Then she said to Henry, “Maybe it was a mistake.”

“How could it be a mistake?” asked Scooter. “It was under Ribsy’s collar, wasn’t it?” He looked at the ticket again. “See, it says here that you have violated a code. The policeman has written the number of the law you broke. I know, because my dad explained it to me once when he got a ticket. Maybe you have to put in more money to park dogs.”

“Maybe they’ll put Ribsy in jail,” suggested Robert.

“No they won’t,” said Henry. “You never heard of them putting a car in jail, did you? This is the same thing.”

“That’s right,” agreed Scooter, and laughed. “Maybe they’ll put you in jail.”

“What do you suppose they’ll do, Henry?” asked Beezus anxiously.

“I don’t know. I guess I’ll have to pay a fine.” Henry stuffed the ticket in his pocket.

“My dad knows a man who knows the mayor,” said Robert. “Maybe he could do something about it.”

“No, I’ll have to take it out of my bike money,” said Henry. “Say, Scoot, how much did your dad pay when he got the ticket?”

“A dollar, I think,” said Scooter. “No, I guess it was two.”

There went at least a dollar from Henry’s bike fund. Maybe two. Two dollars plus a dime for Cheezy Chips. Take that from four dollars and fourteen cents and he had two dollars and four cents left for a bike—that is, if he ever got to the auction and if there were any bikes left when he did get there. Maybe he could get a good sturdy frame and pick up a couple of wheels some place.

“You could ask at the police station,” suggested Beezus.

Why hadn’t he thought of that before? “Hey, kids, let’s go,” said Henry. He didn’t have to untie the twine. Ribsy had chewed it in two.

Scooter pedaled slowly and the others ran along beside him. Even Ramona ran. Eating all the lions out of the animal-cracker box made her forget she had to be wound up.

Henry worried about the ticket. What was wrong with leaving Ribsy outside the supermarket? He couldn’t take him in, so he had to leave him out, didn’t he? And if he didn’t tie him, he wouldn’t stay out, would he? It must be a mistake. It had to be. If only he could get to the station and find out before the auction.

“Wow!” exclaimed Henry, when they finally turned a corner and came to the Glenwood police station. The steps of the building swarmed with children. The driveway beside the station was crammed with boys and girls, and grown-ups, and dogs, too. Other children perched on the fence between the driveway and the apartment house on the other side. More children were getting out of the cars that jammed the streets.

“I’ll go with you to see about the ticket,” Beezus told Henry. Scooter and Robert decided they would try to find a place on the fence.

When Henry made his way through the crowd on the steps, he found a policeman blocking the door. “Around to the side of the building, kids,” he said. “The auction is out in the driveway and no one is allowed to go through the station.”

�

��But I just wanted to ask…” said Henry.

“Run along, everybody,” directed the policeman.

“But…” said Henry.

“Sorry,” said the policeman.

“Come on.” Beezus tugged at Henry’s sleeve. “It’s started already. You can ask afterward.”

“But I won’t know how much money I can spend,” protested Henry, as he followed Beezus. When they reached the driveway, Henry tried to worm his way through the crowd. Maybe he could get to the back door of the police station and ask about his ticket there.

“Hey, quit shoving,” ordered a boy.

“Yes, we were here first,” said another. “Who do you think you are?”

“We’ll never make it to the back door in time. There must be other policemen around some place.” Henry was worried, because he could hear the auctioneer’s voice and knew that bicycles were being sold.

“What am I bid for this bicycle?” Henry heard faintly above the noise of the crowd. He knew he had to get his ticket straightened out pretty soon, or he might as well go home and forget the whole thing.

“There’s a policeman,” exclaimed Beezus. “Over there by the fence.”

When Henry, the two girls, and Ribsy had fought their way through the crowd to the policeman, they found he was too busy trying to get boys off the fence to notice them.

Henry didn’t know how to speak to an officer. “Mr…. uh…Policeman,” he said cautiously.

“All right, boys,” directed the man. “Down off the fence.”

The auctioneer’s voice continued. “Sold!” he shouted.

Henry and Beezus exchanged anxious looks. There went another bike. “Mr. Policeman!” This time Henry spoke louder.

Still the officer did not hear.

Then Ramona marched over to him and tugged at the leg of his uniform. “Hey!” she yelled.

Surprised, the officer looked down at her. “Hello there. Something I can do for you?” he asked.

“Yes.” Henry spoke up. “Uh…this is my dog, Ribsy.”

Ramona Quimby, Age 8

Ramona Quimby, Age 8 Dear Mr. Henshaw

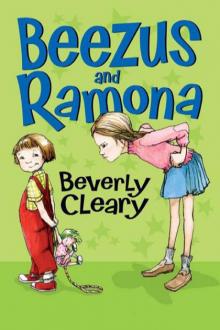

Dear Mr. Henshaw Beezus and Ramona

Beezus and Ramona A Girl from Yamhill

A Girl from Yamhill Ramona Forever

Ramona Forever Jean and Johnny

Jean and Johnny The Luckiest Girl

The Luckiest Girl Emily's Runaway Imagination

Emily's Runaway Imagination Ribsy

Ribsy Ramona the Pest

Ramona the Pest Socks

Socks Ramona's World

Ramona's World Strider

Strider The Mouse and the Motorcycle

The Mouse and the Motorcycle Henry and the Paper Route

Henry and the Paper Route Ramona the Brave

Ramona the Brave Henry Huggins

Henry Huggins Ramona and Her Mother

Ramona and Her Mother Ralph S. Mouse

Ralph S. Mouse Sister of the Bride

Sister of the Bride Henry and the Clubhouse

Henry and the Clubhouse Muggie Maggie

Muggie Maggie Runaway Ralph

Runaway Ralph Ramona and Her Father

Ramona and Her Father Henry and Ribsy

Henry and Ribsy Henry and Beezus

Henry and Beezus Two Times the Fun

Two Times the Fun Fifteen

Fifteen Mitch and Amy

Mitch and Amy